Imagine you’re listening to your favorite song, a symphony, or even just the hum of your refrigerator. What you're experiencing is a complex tapestry of vibrations, each with its own character. Diving into the world of sound means understanding these fundamental building blocks. Today, we're exploring different tone types, specifically the foundational trio: sine, square, and noise waveforms, unraveling how their unique structures shape everything we hear, from a delicate flute note to a roaring synthesizer.

These aren't just abstract scientific concepts; they're the invisible architects of sound, deeply impacting music production, audio engineering, even the way we experience sound therapy.

At a Glance: Understanding the Building Blocks of Sound

- Sound is Vibration: All sound originates from objects vibrating, creating pressure waves in the air.

- Tones vs. Noise: Repetitive, predictable vibrations create tones (pitches). Random, non-periodic vibrations create noise.

- Timbre is Key: Timbre is the "color" or quality of a sound, distinguishing a flute from a violin even if they play the same note. It's largely determined by harmonics.

- Sine Waves: The simplest, purest tone. A single, smooth frequency with no overtones. The foundation of all other complex sounds.

- Square Waves: A complex tone built from a fundamental frequency and only odd harmonics. Known for its hollow, reedy, or woody sound.

- Saw Waves: Another complex tone, composed of a fundamental frequency and all integer harmonics. Produces a bright, buzzing, rich, and often aggressive sound. (Often used in synthesis, though not explicitly in the article title, it's critical context for understanding complex tones).

- Noise: Aperiodic, random sound with no discernible pitch. White, pink, and brown noise are common types, each with different frequency distributions.

- Fourier's Insight: Any complex periodic sound can be broken down (or built up) into a series of simple sine waves at various frequencies and amplitudes.

The Fabric of Sound: Tones, Timbre, and the Invisible Shapes

Before we dissect specific tone types, let's lay a quick foundation. At its core, sound is simply vibration. When an object vibrates, it creates pressure waves that travel through a medium (like air) to our ears. Our brains then interpret these waves as sound.

The nature of that vibration determines the type of sound we perceive:

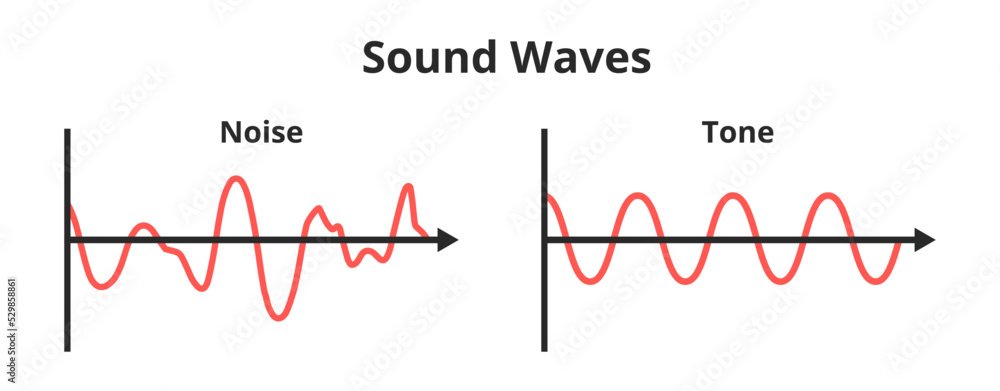

- Periodic Sounds (Tones): When an object vibrates repetitively and predictably, our ears interpret the resulting pressure waves as stable tones or pitches. These are the sounds you can play a tune with, like a piano note or a human voice singing a specific pitch. Traditionally in Western music, a musical tone is a steady, periodic sound, as noted by the Greek philosopher Aristoxenus centuries ago.

- Aperiodic Sounds (Noise): When vibrations are non-periodic and random, we interpret them as noise or atonal sounds. Think of the crash of cymbals, the rustle of leaves, or the hiss of static.

A musical tone is characterized by its duration, pitch, intensity (or loudness), and critically, its timbre. Timbre is the "quality" or "color" of a sound that allows us to distinguish between different instruments playing the same note at the same loudness. A flute and a violin playing middle C sound markedly different, and that difference is primarily due to their timbre.

So, what determines timbre? It's largely about something called harmonics or overtones. Most musical sounds aren't just a single frequency; they're a complex blend. They have a primary, loudest frequency called the fundamental frequency, which our ear perceives as the pitch of the note. But they also contain additional, fainter frequencies that are exact multiples of this fundamental frequency. These multiples are the harmonics. For example, if a note's fundamental frequency is 440 Hz (A4), its harmonics would be 880 Hz, 1320 Hz, 1760 Hz, and so on.

The presence, absence, and relative loudness of these harmonics are what give each sound its unique character or timbre. This concept is incredibly powerful, underpinning much of what we understand about sound synthesis and acoustics. In fact, the Fourier theorem states that any periodic waveform can be accurately approximated as a sum of a series of sine waves at specific frequencies and phase relationships. This means even the most complex instrument sounds are, at their heart, just collections of sine waves!

Now, let's explore the fundamental "shapes" of these sound waves.

The Purest Form: Sine Waves

Imagine the simplest possible sound. No frills, no complexity, just a single, smooth oscillation. That's a sine wave.

- What it is: A simple tone, or pure tone, has a sinusoidal waveform. It represents a single, fundamental frequency vibrating smoothly and periodically. It's the most basic building block of sound, devoid of any harmonics or overtones.

- How it sounds: Clean, clear, and almost eerily pure. It often sounds like a gentle whistle or a tuning fork. Because it lacks harmonics, it doesn't have a rich "character" like an instrument, making it somewhat sterile or hollow on its own.

- Why it matters: Despite its simplicity, the sine wave is profoundly important. As the Fourier theorem suggests, every other periodic sound, no matter how complex, can be mathematically broken down into a series of sine waves. In sound synthesis, sine waves are often used as direct sound sources or as modulators to create other effects. They are also critical for testing audio equipment because of their predictable nature.

The Bold & Blocky: Square Waves

Moving beyond pure simplicity, we encounter complex tones like the square wave. This waveform introduces us to the fascinating world where the presence (or absence) of specific harmonics dramatically shapes timbre.

- What it is: A square wave is characterized by its alternating between two discrete amplitude values, creating a "blocky" appearance. It's not smooth like a sine wave but rather has sharp, instantaneous transitions.

- How it's built: Crucially, a square wave is composed of a fundamental frequency and only its odd harmonics. So, if the fundamental is F, you'll find harmonics at 3F, 5F, 7F, and so on, with their loudness gradually decreasing as their frequency increases. The absence of even harmonics gives it a distinctive sound.

- How it sounds: Square waves have a distinct hollow, reedy, or woody timbre. Think of the sound of a clarinet, which naturally emphasizes odd harmonics, or many classic synth sounds from the 8-bit era of video games. Its crisp, almost "boxy" quality makes it stand out.

- Why it matters: Square waves are ubiquitous in electronic music and sound design. They're a staple for creating basslines, leads, and pads in synthesizers. Their unique harmonic content provides a distinct sonic signature that's easily recognizable and versatile.

The Rich & Rhythmic: Saw Waves

While not explicitly in our title, the saw wave (also known as a sawtooth wave) is another foundational complex tone in digital sound, offering a critical contrast to the square wave and deepening our understanding of timbre. The context research highlights its importance as one of the three basic digital wave types alongside sine and square, making its inclusion essential for a truly comprehensive guide.

- What it is: A saw wave has a shape that linearly ramps up (or down) and then sharply drops (or rises) back to its starting point, creating a jagged, "saw-tooth" appearance.

- How it's built: Unlike the square wave's selective harmonics, a saw wave is composed of a fundamental frequency and all integer harmonics. This means you'll find harmonics at 2F, 3F, 4F, 5F, and so on, with their amplitudes also decreasing as frequency rises.

- How it sounds: Because it contains all harmonics, the saw wave is often described as bright, buzzing, rich, and full-bodied. It can sound aggressive or raw, making it a favorite for powerful synth leads, bass sounds, and orchestral emulations. The richness comes from the full spectrum of harmonic content.

- Why it matters: Saw waves are arguably the most widely used waveform in subtractive synthesis, a common method of creating electronic sounds. Sound designers often start with a saw wave and then use filters to "subtract" certain harmonics, shaping the timbre into something entirely new. It's a powerhouse for creating everything from soaring pads to gritty basses.

Beyond Pitch: The World of Noise

So far, we've focused on periodic sounds – those with a discernible pitch. But what about sounds that lack this regular vibration? Enter noise.

- What it is: Noise is an aperiodic, random sound composed of vibrations that don't repeat in a predictable pattern. It lacks a fundamental frequency, meaning it doesn't have a specific pitch.

- How it sounds: The sound of noise is, by definition, less about pitch and more about its frequency distribution. We typically differentiate noise types by how their energy is spread across the frequency spectrum.

- White Noise: Contains equal energy (or amplitude) at every frequency across the audible spectrum, much like white light contains all colors. It sounds like a constant "hiss" or static.

- Pink Noise: Has equal energy per octave, meaning lower frequencies have more power than higher ones. It sounds "flatter" or more "natural" than white noise, often compared to the sound of a waterfall or steady rain.

- Brownian Noise (Red Noise): Even more energy in the lower frequencies than pink noise, resulting in a deeper, rumbling sound, like a roaring river or deep thunder.

- Why it matters: Noise might seem chaotic, but it's incredibly useful. In audio, it's used to:

- Create Percussion: The sharp attack of a snare drum or hi-hat often relies heavily on noise components.

- Sound Design: Simulating wind, rain, static, or whooshes.

- Masking and Relaxation: White or pink noise generators are popular for masking disruptive background sounds, improving focus, or aiding sleep.

- Acoustic Testing: Used to measure room acoustics or calibrate audio systems due to its broad frequency content.

Why These Waveforms Matter: Real-World Applications

Understanding sine, square, saw, and noise waveforms isn't just academic; it unlocks a deeper appreciation and control over the sounds around us.

- Musical Instruments: Many acoustic instruments, from brass to woodwinds, naturally produce sounds that can be analyzed in terms of their fundamental frequency and harmonic content, often resembling complex combinations of these basic waves. For instance, the hollow sound of a clarinet (emphasizing odd harmonics) can be partially explained by its resemblance to a square wave, while a bowed string (rich in all harmonics) is closer to a saw wave.

- Synthesizers: These waveforms are the very DNA of electronic music. A vast majority of synthesizer patches begin with sine, square, or saw waves, which are then sculpted using filters, envelopes, and effects to create an endless palette of sounds. From the classic basslines of techno to the soaring leads of progressive rock, these foundational shapes are at work.

- Audio Engineering & Acoustics: Engineers use pure sine waves for testing speakers, microphones, and room acoustics. Noise is essential for calibration and analysis. Understanding how different waveforms interact with physical spaces helps design better concert halls and recording studios.

- Psychology & Therapy: The calming properties of white and pink noise for sleep, concentration, or tinnitus relief are well-documented. Online tone generators can be invaluable tools for anyone looking to experiment with these sounds for practical purposes.

- Digital Signal Processing (DSP): Behind every digital audio effect, from reverb to chorus, lies complex mathematical manipulation of these fundamental waveforms. Programmers and audio algorithm designers rely on a deep understanding of these principles.

Shaping Sounds: Synthesis and Sound Design

The journey from a simple sine wave to a complex, evolving pad sound or a punchy bass isn't magic; it's the art and science of synthesis. Here's a quick look at how these waveforms become the starting point for creation:

- Oscillators: At the heart of most synthesizers are "oscillators" that generate these raw waveforms (sine, square, saw, triangle, pulse, etc.) at specific pitches.

- Filters: These allow you to "carve out" frequencies from the rich harmonic content of square or saw waves. Want a warmer sound? Cut the high frequencies. Want a brighter, more aggressive tone? Boost them.

- Envelopes: These shape how a sound changes over time – its attack (how quickly it starts), decay (how quickly it falls to a sustained level), sustain (how long it holds that level), and release (how quickly it fades out after the key is released). This is what makes a plucked string different from a sustained organ note, even if they share the same base waveform.

- Effects: Reverb, delay, chorus, flanger – these effects further manipulate the original waveform and its harmonics, adding space, movement, and texture.

By understanding the inherent harmonic content of sine, square, and saw waves, sound designers can intelligently choose their starting point and apply subsequent processing to achieve a desired timbre. For instance, you wouldn't typically start with a sine wave to create a bright, aggressive synth lead, because it lacks the necessary harmonics for a filter to sculpt. You'd likely begin with a saw wave, rich in all harmonics, and then use a low-pass filter to shape its brilliance.

Common Questions About Tone Types

You might still have some lingering questions as you explore these fundamental sound concepts. Let's tackle a few common ones.

Q: Are there other basic tone types besides sine, square, and saw?

A: Yes! Triangle waves are another very common basic waveform in synthesis, characterized by a smooth, linear ramp up and down. They are similar to square waves in that they primarily contain odd harmonics, but these harmonics decrease in amplitude much faster, giving them a softer, mellower sound closer to a sine wave. Pulse waves (a variable form of square wave) are also widely used.

Q: How do digital and analog synthesizers generate these waves differently?

A: Analog synthesizers generate waveforms using continuous electrical currents, often using circuits with capacitors and resistors. Digital synthesizers generate them using mathematical algorithms and then convert the digital signal into an analog one. While the end result (the sound) can be similar, the underlying generation method is quite different, and each has its own characteristic sonic quirks.

Q: If complex sounds are just sine waves, why not just use sine waves to make all music?

A: Theoretically, you could! But practically, it would be an incredibly tedious and computationally intensive process. Imagine needing hundreds or thousands of individual sine wave generators to perfectly replicate the sound of a single piano note, adjusting each one's frequency, amplitude, and phase. Synthesizers and instruments provide much more efficient ways to generate and manipulate these complex harmonic structures. The Fourier theorem describes analysis and synthesis, but directly constructing sounds from pure sines is often more theoretical than practical for general music creation.

Q: Does noise have a fundamental frequency?

A: No. By definition, noise is aperiodic, meaning it lacks a regular, repeating pattern of vibration. Without this periodicity, there's no identifiable fundamental frequency and, therefore, no perceived pitch. Its energy is spread across a range of frequencies rather than concentrated at specific harmonic points.

Q: How do different tone types affect emotional response?

A: This is a fascinating area! While highly subjective, generally, purer tones (like sine waves) can sometimes evoke a sense of calm or even emptiness due to their lack of complexity. Square and saw waves, with their richer harmonic content, often feel more dynamic, assertive, or even aggressive, especially when played loudly. Noise can range from calming (like pink noise for sleep) to alarming (like sudden static), depending on its context and characteristics. Much of this is tied to the psychological impact of specific harmonic structures and transient behaviors.

Your Sonic Toolbox: Next Steps in Exploration

The journey into the science of sound is endlessly fascinating. From the pure simplicity of a sine wave to the complex textures of noise, these fundamental tone types are the bedrock of our sonic universe. They aren't just abstract concepts but powerful tools that shape our music, our soundscapes, and even our understanding of the world around us.

To truly grasp these concepts, there's no substitute for hands-on experience. Whether you're an aspiring music producer, a curious audiophile, or simply someone who wants to understand the invisible forces at play in every sound, dive in! Experiment with creating sounds using these waveforms, listen to how different filters and effects change their character, and you'll quickly develop an intuitive sense for their unique properties. The more you play, the more you'll uncover the secrets hidden within the airwaves.